(1) designs and implements courses that reflect teacher mastery of their academic discipline and its teaching methodologies

(2) designs and implements courses framed by the school’s pedagogical tenets – inquiry, experience, and integration

(3) collaboratively designs and evolves course curricula that are reflective of their academic discipline’s philosophy and derivative of the school’s overarching philosophy

(4) updates course content to reflect the contemporary world

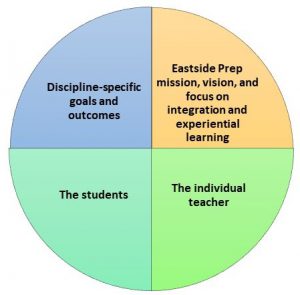

Crafting discipline-specific courses, units, assessments, formative assignments, and daily lessons is one complex layer of curricular design. Good teachers around the world work within this layer to create solid learning experiences for their students.

At Eastside Prep, we add a second layer to our practice which blends together the tenets of our mission, vision, and focus on integration and experiential learning. This layer provides the base from which the rest of our program grows.

Yet another layer has to be the students with whom we work. We have to know the capabilities and interests of the age group, of the individual, of the composition of each class – this is yet another complex layer in creating curriculum.

Experience of the individual teacher is also a critical layer of curricular design. What a teacher knows about her subject dictates the content to a great extent.

(1) designs and implements courses that reflect teacher mastery of their academic discipline and its teaching methodologies

My background is firmly situated in literature. I have been a reader all of my life, my bachelor’s degree is in English Literature, and my graduate degree is in library science. My first real job out of college was as an assistant at a literary agency, where I worked with authors and learned about the business of the publishing world. Exploring the world through story has been my main approach to learning and understanding since childhood.

The Literary Thinking 1 course that I’ve been teaching at EPS for several years applies such an approach to learning and understanding. It is designed as a genre study, moving through nonfiction, historical fiction, mythology, folktale, poetry, and short story (formerly the classic) units throughout the year. Each genre exists in its own unit during which students read exemplars of the genre, learn to identify genre-specific characteristics, and then apply their knowledge to their own writing. In addition to the technical differences of each genre, students explore content and ideas within each genre that help them understand the world around them.

As an example, consider the mythology unit. Students read~ common Greek myths as well as traditional myths from diverse cultures around the world. They compare the stories to find similarities (eg. deities, realms of existence) and differences (eg. geography, cultural beliefs); these discoveries make up the genre-specific characteristics students apply to their reading and writing during the unit. Next, students apply what they have learned to their own culture at EPS. Who are the deities? Where on campus are the various realms? What values bring us together? They put their ideas into writing* EPS Myths, the culminating assessment, where they display what they have learned about the world around them by using story.

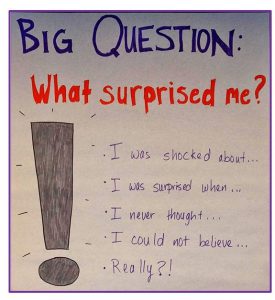

~ Reading: reading for understanding can be a complex endeavor, so I try to impart “tricks” to help students solve comprehension issues. For example, one trick is to ask themselves the “Big Questions” (from Reading Nonfiction) when reading a text. One such question is “What surprised me?”, which can help students focus on what they DO understand and build confidence that they can comprehend even more.

* Writing is always a process: generate ideas –> draft –> revise/edit –> publish. When working through a draft with a student, I most often start by asking them to identify the current stage of writing so they begin to internalize that writing is a process that can be worked through.

(2) designs and implements courses framed by the school’s pedagogical tenets – inquiry, experience, and integration

My background as a teacher has taken place singly at Eastside Prep, where I have had instilled in me the tenets of inquiry, experience, and integration as necessary foundations for effective learning. I write above about how I incorporate English language instruction into teaching the mythology unit; those techniques layer on top of my focus on inquiry, experience, and integration as I design the unit (as with all units I teach). Building inquiry into lessons gives students ownership of the material; if they have to engage to the point of asking questions, of making connections on their own, they view the content more intimately than if I just lectured the content to them. As in the mythology unit above, students have to read original myths to discern commonalities; I don’t give them the list of traditional elements, but rather we create the list together. Experience offers another layer of ownership in that when you do something you learn it in deeper ways. Myths, for instance, were originally written to explain the unknown; during the unit, I provide students with an “unknown” sound (listen below!) and give them the opportunity to explain it with drawings (sketch the creature that might make that sound!), thereby experiencing the basis for the creation of a myth and gaining firsthand understanding of the tradition. The process of integration widens understanding of content by relating it to other known experiences. The mythology unit (good ol’ example), overlaps with the study of ancient worlds in the Historical Thinking 1 course, where students learn about the governments, social structures, and geography as a compliment to the belief structure of the myths. Inquiry, experience, and integration form the basis of all courses at Eastside Prep because we believe they are processes by which students learn best.

(3) collaboratively designs and evolves course curricula that are reflective of their academic discipline’s philosophy and derivative of the school’s overarching philosophy

Since the beginning of the school in 2003, the overlap of content and methodologies between disciplines has been at the core of what we do at Eastside Prep. We know that ideas in the real world don’t exist in isolation, that they cross industry, geographical boundaries, etc., so we want to show our students this complexity as a reality in their world, too. We want students to think about each topic from many perspectives.

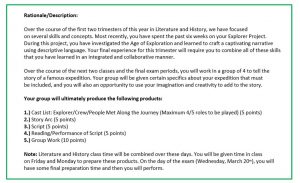

One of the many integrated, experiential, and inquiry-based projects I have created with colleagues over the years is a “final” that we use to wrap up a couple of different 5th-grade units during the winter term.

In Intro to Literary Thinking, we read the script adaptation of the book The Westing Game to round out our unit on the mystery genre. The script format allows students to experience a written story in a different way: we set up chairs in a “readers’ theater” circle and orally read the script together; students take turns reading different roles; and we work together as a class to make predictions about outcomes.

In Intro to Historical Thinking (the 5th-grade history course that Anthony Colello teaches), students complete a weeks-long research project about the world’s great explorers. They practice finding facts, taking notes, organizing ideas, and presenting their own interpretation of events in a written assessment. (Technically, there is a highly collaborative aspect here, too, with Intro to Lit but that’s an explanation for a different day.)

For the integrated “final,” we combine the skills practiced in each of these units into a single project: a scene about a made-up explorer in a real time period written in script format. Over the course of three days, we:

For the integrated “final,” we combine the skills practiced in each of these units into a single project: a scene about a made-up explorer in a real time period written in script format. Over the course of three days, we:

- split our blended classes into small, tailored groups,

- provide each group with a real place and time period in which to set their story, and

- turn them loose to create characters (explorers, scientists, navigators, etc.), plot, and story lines.

The project culminates with a live enactment of the script.

The endeavor is not only super fun for the students, Anthony, and myself, but is also firmly rooted in the Eastside Prep philosophies of integration, experiential education, and critical thinking, as well as in the philosophies of each of our respective disciplines. Students use the writing process to craft complete stories and communicate ideas; they research for facts about the real time periods and geographical settings; and they work together, using each other’s ideas and skills to create story, props, and stage direction.

(4) updates course content to reflect the contemporary world

There are always multiple ways to incorporate events from the contemporary world into an English classroom. Texts from contemporary authors and thinkers come to mind, especially as they relate to the themes and content of what students are studying. One such example came about in the fall of 2019 as 6th-grade students focused on the elements of the nonfiction genre. One of the reading “tricks” I was teaching was to notice “extreme or absolute language” in a text; once found, I asked students to pause and consider why the author chose that language. Why did they use “best” rather than “good,” “eliminates exception” rather than “stops?” The technique (from Reading Nonfiction) is intended to help students pause and think more deeply about the text. That same week, teen activist Greta Thunberg addressed the United Nations regarding climate change. Her speech was full of extreme and absolute language, she was making an impact on the world in that moment, and she was a child, just a little older than my 6th graders. What could be more timely and appropriate than to have them read a transcript of Thunberg’s speech (a work of nonfiction from a person of the same generation) that was chock full of examples of extreme language?

Students explored the transcript in small groups, “discussing” the piece in silence by writing their ideas onto a central poster (see left). Each student’s ideas were written in a unique color, so one could track a single student’s line of thinking. I asked students to use nonfiction reading techniques (Big Questions and extreme language, for instance) to guide their “discussion,” but eventually their own conversations developed through analysis of the text and the situation at large. This opportunity to explore a current event within the context of the classroom environment had a significant impact, and inspired some students to get involved with the middle school “walkout” that happened on campus the following week.