(1) begins class sessions with a clear statement about the lesson’s objectives and place in the progression of course

(2) designs and implements varied activities in each class period

(3) brings each activity to closure effectively and transitions intentionally to subsequent activities

(4) ensures that students are using technology and tools effectively

(5) concludes class with a summary and clear tie-in to the next class

Setting up routines, common practices, and clear expectations has been a focus of mine since I started teaching middle schoolers. I believe that pedagogical effectiveness in a 5th- or 6th-grade classroom is built upon these foundations; they build comfort and predictability, lessen surprise, and help students focus on the learning rather than on how they should behave. Such fundamentals allow me to “disrupt” practices, too, so that I can continue to expand the capabilities and capacities of my students while still providing them with a feeling of safety.

Examples of Routines

- OneNote agenda and lessons for each class period

- Closing laptop at beginning of clas

- Break worked into the 85-min block period

Examples of Common Practices

- Date on clean page in writing journal

- Handwriting in writing journal (instead of typing) during the drafting stage of the writing process

- Identifying stages of writing when we write – brainstorming, drafting, revising, etc.

- Heading on Word docs

- Recurring activities such as Station Rotation, group work, Attendance Question

Examples of Clear Expectations

- Set at beginning of year OR the first time we do a new activity, and then constant reminders

- Laptop use guidelines

- Discussion guidelines like listening and taking turns

- Written directions at stations (added in quiet/discussion/moving directions, as well as time keeper and quality control roles)

These structures, once in place, gives me freedom to vary learning experiences in each class period. None of the class periods look the same, different activities to match the learning, keep kids moving forward.

(1) begins class sessions with a clear statement about the lesson’s objectives and place in the progression of course

Every day as students enter my classroom, they see the day’s agenda projected on the board. The agenda is crafted on a OneNote page, and includes the topics and activities that will take place during the period as well as the homework that was due that day. Students settle into chairs knowing what is coming up and remembering what needs to be turned in, and they don’t have to ask the inevitable question, “What are we doing today?” When class begins, we read through each item on the agenda and I add detail as necessary, such as how the activities fit into the progression of the class (although sometimes that comes out during the activity rather than at the beginning of class). Each item on the agenda is coded in a different color, and the color matches up with the lesson further down the page (for the visual learners and the nerdy librarian in me).

Every day as students enter my classroom, they see the day’s agenda projected on the board. The agenda is crafted on a OneNote page, and includes the topics and activities that will take place during the period as well as the homework that was due that day. Students settle into chairs knowing what is coming up and remembering what needs to be turned in, and they don’t have to ask the inevitable question, “What are we doing today?” When class begins, we read through each item on the agenda and I add detail as necessary, such as how the activities fit into the progression of the class (although sometimes that comes out during the activity rather than at the beginning of class). Each item on the agenda is coded in a different color, and the color matches up with the lesson further down the page (for the visual learners and the nerdy librarian in me).

Why do I choose to do my agenda this way? Firstly, consistency. Students see the same format every day and they come to know what to expect. Secondly, transparency because I want my students to know what’s coming and give them time to process and prepare for the coming work. Thirdly, OneNote is super easy to alter if the need arises, and I appreciate this adaptable kind of format. Lastly, OneNote is also super easy to share with my students, which gives them access to the details of every class.

(2) designs and implements varied activities in each class period

Varying activities and learning modes during each block period is critical in a middle school classroom. The attention spans of 10- to 12-year-olds is not long, so to make the most of our time together I regularly change up the activities. My goal for most classes is for students to experience some mix of talking, writing, and reading (content), as well as a mix of technology (mode) and opportunities for movement. The artifact for this section – a snapshot of a OneNote agenda – shows an intentional balance of these varied activities.

Varying activities and learning modes during each block period is critical in a middle school classroom. The attention spans of 10- to 12-year-olds is not long, so to make the most of our time together I regularly change up the activities. My goal for most classes is for students to experience some mix of talking, writing, and reading (content), as well as a mix of technology (mode) and opportunities for movement. The artifact for this section – a snapshot of a OneNote agenda – shows an intentional balance of these varied activities.

The content of each class period is most typically based on a trio of literary skills: writing, reading, and discussion. In the sample agenda, it becomes clear that writing is spread out over a couple of activities – the survey and the Writing Workshop – and gives students the chance to practice a variety of writing styles. Choice is also a critical component in each class period, and the Writing Workshop is designed to let the students select where they are in the writing process and work from that point. Reading practice comes during the Reader’s Theatre portion of class as we orally read the script of the stage version of The Westing Game together as a class. We set up chairs in a large circle (movement!), roles are assigned, and everyone follows along in the script as the story unfolds. We pause the reading for questions, comments, and to make predictions, which is part of reading comprehension and also part of discussion skills; as with each day’s Attendance Question, students practice listening to each other, finding connections between ideas, and contributing to the greater understanding of the text. This blend of content makes most classes go by really quickly!

A balance of technology is also important so that students get practice using a variety of tools. Some parts of class require “newer” technology, such as laptops, while other parts of class need “older” technology like paper and pencils. In the sample agenda, the Attendance Question and journal writing are laptop-free exercises; the online survey obviously requires a laptop, and so does Reader’s Theatre since the script is posted in our shared Content Library in OneNote.

I also try to find moments for movement during each class period. Most often they occur during transitions between activities when students move chairs, put away writing journals, etc. I work a brain break into most class periods, too, allowing students to get fresh air, stretch their legs, use the restroom, or fuel their bodies with water and a snack.

(3) brings each activity to closure effectively and transitions intentionally to subsequent activities

Successfully wrapping up one activity and beginning another during the block period without losing student focus and/or instruction time can feel like a magic trick. Show students something shiny with one hand and, with the other, sneak in a new job or assignment without them noticing. The flow of class smoothly rolls on.

Successfully wrapping up one activity and beginning another during the block period without losing student focus and/or instruction time can feel like a magic trick. Show students something shiny with one hand and, with the other, sneak in a new job or assignment without them noticing. The flow of class smoothly rolls on.

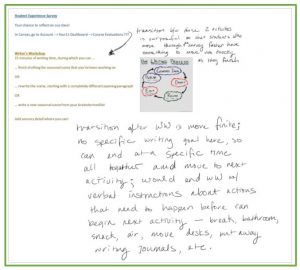

That happens sometimes.

What happens more often is that I give explicit directions, verbally and visually, as I introduce and end each activity … and then I keep my fingers crossed that I have provided my students enough guidance along the way to make the transition with minimal extra support from me. The snippet from an Intro to Lit agenda shows a couple methods of transition. One activity (Student Experience Survey) flows right into the next (Writer’s Workshop); the timing of when the Survey ends and the Writer’s Workshop begins depends entirely on the speed and thoroughness of the individual student, providing necessary allowances for the variety of learners. Finishing up the Writer’s Workshop, though, is a hard stop; we end the activity at the same time so that we can move into the following group activity all together. During this specific class period, I communicated directions for both activities at the same time so that work time could be fluid. Transitions are never as smooth as practiced magic tricks, but we continue to practice them during every class.

(4) ensures that students are using technology and tools effectively

When I think about “effective” use of technology, a couple of distinctions come to mind. Effectiveness can be attributed to how well students behave when using technology: are they doing what I asked, or are they messaging a friend? Effectivenss can also be assessed when considering how competent students are at using technology: can they submit an assignment in Canvas? One focus is on behavior management, while the second is on function.

As I think about how I help students manage their behavior when it comes to technology, I start by trying to set and reiterate clear expectations. I give verbal reminders:

- “When you have your laptop open in my class, I expect and believe that you are working on what you’re supposed to be working on.”

- “The only program that should be open is …”

- “Close laptops when you’re working on …”

“If you’re following along on your laptop, it needs to be in tablet mode.”

“If you’re following along on your laptop, it needs to be in tablet mode.”

I employ the “classroom management by physical proximity” technique, moving around the room to keep an eye on tech use (and focus). And I redirect behavior when necessary; sometimes that happens in a classroom-wide manner (“I’ve noticed that several of you have a message screen open …”), and sometimes as a one-on-one interaction (“Mr. Uzwack, can I have a quick conversation with you?”). Redirection is rarely punitive in my classroom; instead of, say, taking away a laptop because a student is messaging her friend in another class, I try to acknowledge the temptation, empathize with her, and help her find ways to work around it. Students will be using tech tools all of their lives, so encouraging positive habits when they are young can positively impact tech use as they grow older.

As I think about helping students use tech tools in a “functional” manner – do they know how to access my feedback on Canvas? Do they know how to format a document in Word? Can they save a document to their OneDrive account? – I find that providing concrete, direct, and visual examples for students to follow (see the step-by-step directions about how to format a Word doc) is especially useful. The document to the right is a sample of directions I printed out for a Station Rotation; in small groups, students could format their pages and use each other for help if needed.

(5) concludes class with a summary and clear tie-in to the next class

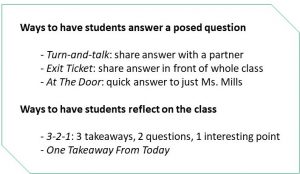

Concluding each class period effectively is an aspect of my teaching practice that I desire to improve. I already save the last few minutes of almost every class period to wrap up, and use a variety of methods to do so, such as:

- Verbally reminding students what is coming up next class (CW or HW)

- Asking an exit question about something they’ve produced or learned during class OR about something fun that’s coming up for them

- Excusing table groups one at a time when ready (part of setting expectations)

Just as Attendance Question begins every class, though, I would like to find a consistent practice that ends my classes. I imagine it would be a specific item on the daily agenda that, when we arrive at it, visually indicates to students that class is almost officially done. Just a single item left to complete. No need for students to ask, “Can we leave now?” Ideas have been percolating in my mind since the Stay Home, Stay Safe order (see image to the left), and I look forward to trying them out when we return to in-person learning. Concluding together in a “formal” and consistent way would provide a welcome bookend to each class period.