(1) considers and addresses each student’s learning profile

(2) designs class activities and assignments that engage and accommodate for both individual students and a diverse group of learners

(3) builds in opportunities for each student to contribute during each class period

(4) provides alternative explanations of course concepts

(5) adapts instruction based on formative assessment

Differentiating instruction and assessment for my students relies on an intentional blending of teaching methods and knowledge of my individual students. I have to know what kinds of learners are in my classroom AND I have to apply my experiences and resources to them to best reach each of the students.

(1) considers and addresses each student’s learning profile

The most important place to begin to differentiate instruction and assessment is to figure out how each of my students learn. Such learning might come in the form of notes from prior teachers, my own observations in the classroom, or conversations with current teachers, parents, or the students themselves. Each learning profile is unique, and it is my job to learn – and then teach to – each one. When one student excels at spelling and grammar, say, but struggles to brainstorm ideas, and another student has great ideas but struggles to write them legibly on the page, it falls to me as their teacher to identify those strengths and challenges, and then adapt, or differentiate, my support for both students. Now consider that there are eighteen unique profiles in a single classroom, and therein lies the real work of a classroom teacher.

Once the work of learning each student’s profile gets underway (it never ends because I’m always learning something new and the students are always growing), my bank of teaching methods comes into play. I dive into past experiences to cull ideas to then adapt to current situations. I connect with colleagues, such as the Student Support teachers, who offer guidance about processes that have worked for similar learners in the past. I vary daily class activities to try to connect to the varied learning styles and strengths of my students; we move, we read, we talk, we sketch, we write. I offer options within projects in the hopes that each student can find a “best fit” outlet to share what they know. I curate small groups to maximize learning styles, personalities, and strengths. I have direct conversations with individual students to talk about how I see them as learners, and invite them to work with me to figure out how best to approach assignments. I support accommodations (formalized or not) and make every attempt to normalize them. There are, likely, many more methods that I use to reach the variety of learning profiles in each of my classes.

(2) designs class activities and assignments that engage and accommodate for both individual students and a diverse group of learners

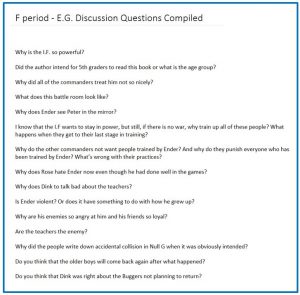

An example of a class activity intended to engage and accommodate individual students and the group as a whole is a sequence of reading, creating questions, and discussing a chapter from Ender’s Game, which we read each spring in Intro to Lit. The sequence goes as follows:

- Students read a chapter of Ender’s Game, usually as homework

- Individually, each student writes 3-5 discussion questions* and turns them in to a Canvas assignment

- I cull through the questions and create a master list of the most relevant/interesting

- Students discuss answers to the questions in small groups^

- Small group answers are shared out to the whole class

I find that this type of activity typically reaches a wide swath of learners. Slow readers can take their time; fast readers have to pause to craft thoughtful questions. Quiet students are often more willing to speak up in smaller groups, or they can contribute by taking on the silent role of recorder. Students who struggle with reading comprehension get to hear what classmates think, and can work out their own ideas in a small-group setting. Students who struggle with handwriting can just talk out their ideas without having to worry about perfect wording or penmanship. Most types of learners can find a comfortable role to play in this activity.

* Discussion questions can include ones that help with understanding content; dive into a theme, scene, character, or plot point; or connect new ideas with other parts of the story, or material in other classes.

^ Groups are crafted to balance personalities, learning styles, strengths, etc. I ask students to each pick a role to play in their group: recorder, reporter, timekeeper and/or eraser. We move through questions one at a time as a whole class; discussion happens within small group, where they record ideas on personal whiteboards, and then they share ideas with whole class.

(3) builds in opportunities for each student to contribute during each class period

Contributions by students in the classroom setting can be exemplified in many ways: raising a hand to verbally share an idea, listening attentively to someone else’s story, acting as the notetaker in a small group, handing out materials, turning and talking about an idea with a partner … the list goes on. My classes almost always incorporate a variety of ways in which a student can contribute, but a specific one that gets everyone talking, listening, and engaged at the same time is Attendance Question.

Every class begins with an Attendance Question: a question to be answered or a prompt to be completed. The question may be relevant to class content (practice a skill learned in an earlier class, generate ideas on a topic, glean student comprehension of course material, etc.) or not (something great/awful that happened over the weekend). I call on one volunteer to “start us off” and then students follow class roster order to continue the flow. Everyone must answer verbally, although I offer “Pass” as an option if the question is somewhat personal.

That’s it. A simple opportunity to contribute during class … that is also sneakily filled with social and emotional skills. Attendance Question includes everyone, limits the need to volunteer, and provides opportunity for students to lead and take responsibility for each other. It lets students practice making decisions (“would you rather” or “pick your favorite …”), taking a risk without a serious consequence, listening, sharing, taking turns, telling their truths, and learning the truths of others. So. Deceptively. Robust!

(4) provides alternative explanations of course concepts

Since student learning styles vary, so must my methods of explaining course concepts. I typically teach a new concept one way (always with a combination of visual and verbal cues), and then provide examples so students can see what the concept might look like in practice. I encourage questions; I provide time in class for students to practice using the concept; and I circulate and observe, offering guidance, corrections, and alternative explanations as needed. If I make the same correction to three or four students, I will often pause the activity to go over the correction with everyone; clearly, more guidance (a mini lesson, if you will) on my part is necessary. As in most academic disciplines, concepts and ideas build upon one another, which means that students will likely be exposed to concepts repeatedly throughout the year, adding yet more alternative means of exploring concepts.

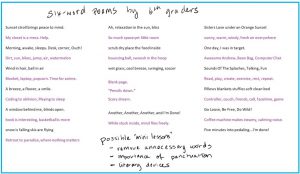

I have also found it effective to teach concepts by having students do the “teaching” or “grading.” A favorite activity of my students is to help me improve my own writing, for instance. If the concept is adding imagery to our writing, I might post a sample of my writing (see left) and ask students for suggestions about where I might include a visual or auditory detail. I write down their ideas (modeling revision and editing techniques, too) until they run out of suggestions, and then I thank them for helping “teach” me how to improve my piece. Another favorite activity is students use a rubric to “grade” someone else’s work. In order to use the rubric well and give good feedback, students have to understand each point on the rubric and be able to identify and evaluate it in someone else’s work. If they don’t understand something, they ask – they’re much more willing to ask for help when it’s not directly connected to their own writing. In doing so, they learn the concepts in a different (and deeper) way.

I have also found it effective to teach concepts by having students do the “teaching” or “grading.” A favorite activity of my students is to help me improve my own writing, for instance. If the concept is adding imagery to our writing, I might post a sample of my writing (see left) and ask students for suggestions about where I might include a visual or auditory detail. I write down their ideas (modeling revision and editing techniques, too) until they run out of suggestions, and then I thank them for helping “teach” me how to improve my piece. Another favorite activity is students use a rubric to “grade” someone else’s work. In order to use the rubric well and give good feedback, students have to understand each point on the rubric and be able to identify and evaluate it in someone else’s work. If they don’t understand something, they ask – they’re much more willing to ask for help when it’s not directly connected to their own writing. In doing so, they learn the concepts in a different (and deeper) way.

(5) adapts instruction based on formative assessment

Every unit I teach begins with a pretty comprehensive plan of what I intend to do with my students: outcomes, projects, lessons, daily assignments, etc. I say “pretty comprehensive” because no plan can be complete without making sure that my students understand the material along the way. Formative assessments come into play throughout a unit so that I can ascertain what students are or aren’t learning; I then use that information to adapt my instruction. I do not give quizzes, but rather use homework/classwork assignments, in-person meetings, and informal methods (like Attendance Question!) to assess formative learning.

A new favorite method of assessing student work is meeting one-on-one with each student during a class period, most commonly during a Station Rotation. During our couple of minutes together, a student shows me what they have completed; I can then assess what they’ve learned, and give them feedback about next steps. There is no grade involved, so the meeting really just allows me to assess their learning and adapt my teaching.

The “six-word poem” image to the right was created by me during our poetry unit this year. Students had turned in a “six-word poem” via Canvas; initially, I compiled the submissions to share the collected work with the whole class, to show them the variety of ideas and approaches used by their classmates. As I reviewed the poems myself, though, I was able to make some observations that eventually turned into future lessons: remove unnecessary words, punctuation placement is important, and literary devices are a writer’s friend. Formative (and informal) assessment guides me yet again.