(1) designs major assessments that reflect course outcomes and posts them at the start of each trimester

(2) designs assignments to be graded and returned in a feedback cycle of seven calendar days

(3) ensures the number of assignments in each course is neither excessive nor deficient — providing appropriate time for quality student performance and meaningful teacher feedback

I consider assessment of student work to be a necessary evil. Necessary because a large part of my job as a teacher is, of course, to help students show what they know and learn where and how to grow. Evil because traditional methods for grading are time consuming, subjective (to a large degree in the English discipline), and don’t always provide the right kind of feedback (product instead of process), among a great many other defects. In order to maximize the necessary elements and minimize the evil ones, I have tried to re-imagine my assessment practices over the past few years.

A few examples of my current assessment practice:

- Breaking down large assignments into smaller parts. This practice helps isolate skills and techniques that students can practice one at a time. It also allows me to assess skills one at a time, and identify what needs more cultivation and when it’s time to move forward to the next skill.

- More student reflection and less teacher feedback. Instead of always relying on me to assess their work, students in my classes work toward more autonomy in their writing and reading practices. I provide them with rubrics, checklists, writing groups of peers, and lessons, and then teach them how to use those resources to further their own abilities. Students learn to review and revise their own work, thereby building confidence in their own literary skills.

- Process, rather than product, feedback. Actionable, targeted feedback given during the writing process provides guidance that students can immediately apply to their work. Traditional practice has the teacher providing feedback after the product has been turned in, when a student cannot do anything with it. The Station Rotation model gives me time within a class period to meet with each student, review their writing, and provide immediate guidance as to what they need to work on. Rather than hope that students use my feedback on a future project, I can see the feedback being used in the current assignment.

(1) designs major assessments that reflect course outcomes and posts them at the start of each trimester

Almost all of the major assessments in my classes are “reverse engineered.” I start designing (or redesigning) them at the beginning of each new unit as I consider the outcomes I want my students to achieve. Once I know the outcomes, I work backward to figure out final assessment –> steps to get there –> flow of lessons and activities –> introduction.

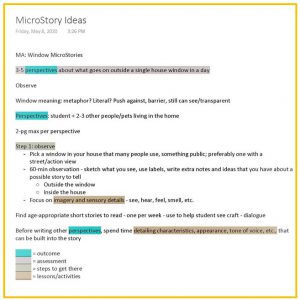

An example of such a design can be seen in the “MicroStory Ideas” notes page. After switching to EPSRemote for the Spring 2020 trimester, Alicia Hale (LT1 teaching partner) and I knew that we would need to redesign the final unit of the school year; exploring The Adventures of Tom Sawyer for character development and episodic stories-within-stories was the usual year-ending unit but it was tough to teach in person, let alone in a distance learning format. So, we started our redesign with “perspective” as the potential outcome and worked backward from there. Alicia had recently read a collection of short stories that explored a single period of time from the perspectives of multiple neighborhood residents, and we adapted that idea to create the final assessment. From there, we filled in the other details – kinds of lessons we would need, how much time we had, where to start – and set the plan in motion. This method of designing a new unit exemplifies my process for creating most of my courses.

An example of such a design can be seen in the “MicroStory Ideas” notes page. After switching to EPSRemote for the Spring 2020 trimester, Alicia Hale (LT1 teaching partner) and I knew that we would need to redesign the final unit of the school year; exploring The Adventures of Tom Sawyer for character development and episodic stories-within-stories was the usual year-ending unit but it was tough to teach in person, let alone in a distance learning format. So, we started our redesign with “perspective” as the potential outcome and worked backward from there. Alicia had recently read a collection of short stories that explored a single period of time from the perspectives of multiple neighborhood residents, and we adapted that idea to create the final assessment. From there, we filled in the other details – kinds of lessons we would need, how much time we had, where to start – and set the plan in motion. This method of designing a new unit exemplifies my process for creating most of my courses.

(2) designs assignments to be graded and returned in a feedback cycle of seven calendar days

Smaller, formative assignments are targeted to help students practice one or two skills at a time. I most often grade these assignments as complete/incomplete; since they are being used as practice, I grade for completion and attempt at the skill(s) rather than for mastery. I will often provide brief notes on these small assignments, with either suggestions for next steps or kudos for their work. Such formative assignments also serve the purpose of informing me what else students need to learn, and I use that information to design upcoming lessons (a more encompassing form of feedback). These types of assignments can be graded in a matter of hours or days.

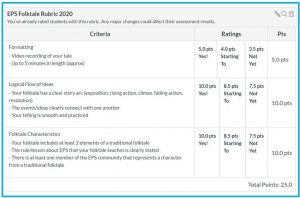

Larger, comprehensive summative assignments are much more difficult to turn around within seven days. I use detailed Canvas rubrics to “check off” the basic requirements of such assignments; I limit the number of elements to grade; the one-on-one meetings I can have with students using the Station Rotation model lessens the amount of written feedback I need to provide; I schedule time on my calendar to just sit and get the grading done. However, I’ve learned that the difficulty is not in the physical act of grading; for me, the difficulty is mental. Grading thirty-six stories for the same elements is tiresome. Writing the same piece of feedback five or more times is just boring (no matter that it gives me direction for future lessons). Even as I have applied my new assessment practices (more student-directed, narrowed focus, feedback during the writing process), I have not yet been successful at changing my attitude toward grading summative assessments. This is an area in which I can still grow as I continue to seek out alternatives.

Larger, comprehensive summative assignments are much more difficult to turn around within seven days. I use detailed Canvas rubrics to “check off” the basic requirements of such assignments; I limit the number of elements to grade; the one-on-one meetings I can have with students using the Station Rotation model lessens the amount of written feedback I need to provide; I schedule time on my calendar to just sit and get the grading done. However, I’ve learned that the difficulty is not in the physical act of grading; for me, the difficulty is mental. Grading thirty-six stories for the same elements is tiresome. Writing the same piece of feedback five or more times is just boring (no matter that it gives me direction for future lessons). Even as I have applied my new assessment practices (more student-directed, narrowed focus, feedback during the writing process), I have not yet been successful at changing my attitude toward grading summative assessments. This is an area in which I can still grow as I continue to seek out alternatives.

(3) ensures the number of assignments in each course is neither excessive nor deficient — providing appropriate time for quality student performance and meaningful teacher feedback

The number of assignments given in my classes is typically based on the length of a given unit, desired outcomes, and the age and abilities of the students. As an example, Literary Thinking 1 is broken down into six genres, which means six approximately equal units spread across the school year. Planning for two units per trimester means that each genre gets 5-6 weeks of study and practice. If the outcome of, say, the nonfiction genre is to be able to identify and use at least five common techniques of an opinion essay, that means that I give students 5-6 weeks to explore such techniques. Sixth graders are 11- and 12-years-old and, while they consume more quickly than fifth graders, I know that they need at least a day to study and practice each technique. All of these factors play together as I prepare each unit, each assignment, each lesson, each interaction with students. And, of course, I pay attention to the quality of the work being turned in and make adjustments to the work load accordingly.

The number of assignments given in my classes is typically based on the length of a given unit, desired outcomes, and the age and abilities of the students. As an example, Literary Thinking 1 is broken down into six genres, which means six approximately equal units spread across the school year. Planning for two units per trimester means that each genre gets 5-6 weeks of study and practice. If the outcome of, say, the nonfiction genre is to be able to identify and use at least five common techniques of an opinion essay, that means that I give students 5-6 weeks to explore such techniques. Sixth graders are 11- and 12-years-old and, while they consume more quickly than fifth graders, I know that they need at least a day to study and practice each technique. All of these factors play together as I prepare each unit, each assignment, each lesson, each interaction with students. And, of course, I pay attention to the quality of the work being turned in and make adjustments to the work load accordingly.

In addition to the work load of the student, I try to also keep in mind my own amount of work to be done. As I assign work to students, I also consider the questions, Is this something I will need to grade or give feedback about? If the answer is yes, I then ask myself, When will I find/make time to do that work?

Good work